Early Painting

Sonya Rapoport earned her MA in Painting at the UC Berkeley Department of Art in 1949, building on her experience at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, DC and the Art Students League in New York. She was the first woman to earn her masters from the department, which she attended concurrently with painters Jay DeFeo, Nancy Genn, and Sam Francis.

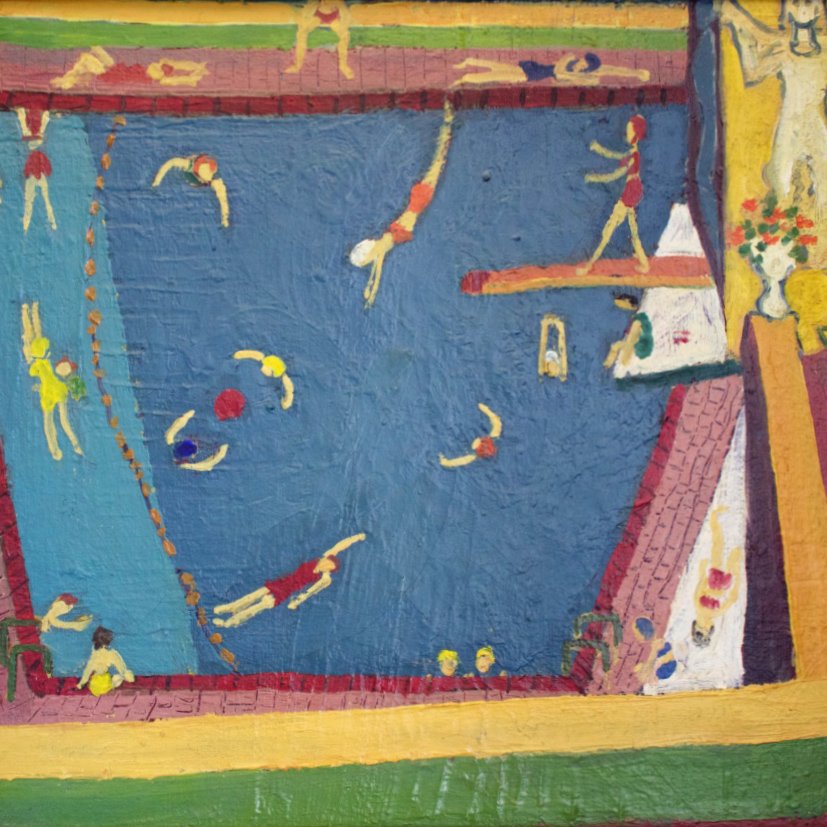

When Rapoport enrolled at Berkeley she had been creating paintings in a faux-naïve style, focusing on domestic interior scenes. At Berkeley, the prevailing pedagogical influence was abstract painter Han Hoffman, whose color sense and vocabulary–push-pull, negative space–would leave a lasting imprint on her practice. Her mentor was painter Erle Loran, whose book “Cezanne’s Compositions” (1943) espoused an uber-formalist approach to constructing a picture plane (Rapoport would later appropriate Loran's compositional diagrams in her artist's book, Chelate (1981)).

Following her graduation, Rapoport associated with the community of artists referred to as The Berkeley School, although she described this relationship as conflicted. Her early career saw her experimenting with figurative abstraction, primarily working in watercolor and oil, with her first solo exhibition at East & West Gallery in San Francisco in 1958. As the early 1960s unfolded, Rapoport transitioned to creating large-scale oil paintings on canvas–thick, gestural, painterly abstractions with vividly hued palettes and compositions that hinted at floral arrangements. In her own words:

“I poured my guts out on canvas, metaphorically speaking, while mixing oil painting with child rearing. One critic called the work ‘a huge bouquet of unruly flowers’, others said I was dispensing Manzoni cow-patties. I see the work as floral feces.”

Sonya Rapoport, from unpublished autobiographical text, “Purple History,” circa 2010.

Rapoport first gained wider recognition with an extensive solo exhibition of her Abstract Expressionist oil paintings at the prestigious California Palace of the Legion of Honor in 1963. Although the work was received positively by critics, Rapoport felt alienated by what she perceived as the anti-intellectualism of her peers and disparagements based solely on her gender. This contributed to her diversion from the Berkeley School paradigm. Moving forward, she would create more challenging and experimental work, with the support of the John Bolles Gallery in San Francisco.