For several years, beginning in 1958, Rapoport expanded on her earlier gestural abstractions to paint in the abstract expressionist idiom, culminating in a prestigious solo exhibition at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in 1963. This exhibition was met with some acclaim, and her work continues to be shown in exhibitions exploring second-wave and West Coast Abstract Expressionism, although, as was typical for her practice, Rapoport was not particularly close with artists associated with these movements, and would move on to more radical painting techniques by 1964.

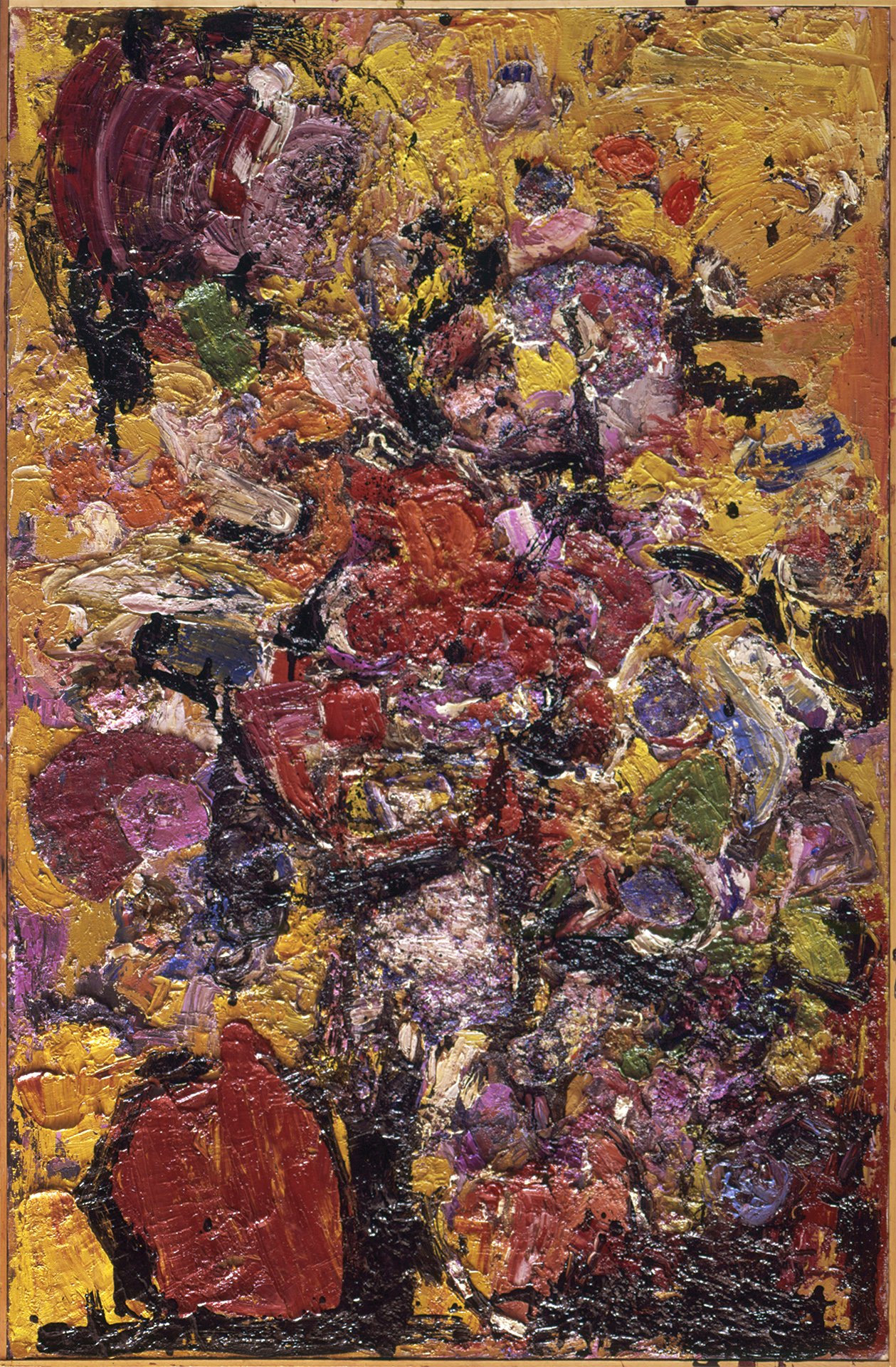

The series of paintings exhibited at the Legion of Honor are all-over abstract compositions; impasto paintings built up with brush, knife, and paint squeezed directly from the tube. They display a frenetic but contained energy that weaves together complex figure/ground ambiguities. Thick, almost sculptural encrustations of agglomerated paint contrast with loose brushwork and finger-smeared passages of plastic paint built up on the canvas.

Rapoport’s color choice and compositions work together to create a sense of space - Hans Hoffman’s theories about color and space continue to serve as a useful key to deciphering this work. However, some of these paintings, i.e. Untitled 20, appear to contain rectangular swatches of canvas fixed to the surface, possibly cut-up older paintings. A no-no for conservative painting purists at the time, this may be the first hint of Rapoport’s interest in making use of unusual substrates and found objects, one that would characterize her work throughout the sixties and seventies. This recontextualization of older work is a tactic Rapoport would continue to use throughout her practice.

The compositions, which at first appear non-objective, hint more or less evidently at floral imagery. Her sometimes prominent use of violets and pinks, and titles that hint at the female body such as Oviform may have been a nod towards the way gender circumscribed the roles she played as a member of the Berkeley academic community, and the male-dominated Berkeley School. Although, as titles such as Capoeira and Jardim Botanico attest, this might just as easily reflect her recent experience of living in tropical Brazil, where her husband had a research residency.

Although the exhibition at the Legion of Honor was received positively by critics, Rapoport was chagrined by her peers’ and mentors’ criticisms, which always seemed to begin by commenting on her gender. This marked a turning point after which Rapoport moved away from the ideas of The Berkeley School and began exploring gender through increasingly radical work, eventually leading to her reinvention as an artist experimenting with new materials and media to explore feminist ideas.

Sonya Rapoport at the opening of her exhibition at the Legion of Honor, 1963.