Computer Printout Drawings

In early 1976, Sonya Rapoport chanced on a box of discarded computer printouts in the basement of the UC Berkeley Math Department, a find which eventually led to her reinvention as a digital artist.

Rapoport, who had been working on found materials since the mid-1960s, was instantly attracted to these complex, coded analyses of information printed in carbon-black, standardized font, on wide-format, ruled, perforated, continuous feed printout paper. This was the era of mainframe computers programmed with punch cards, and the papers had a futuristic and enigmatic appearance.

Initially, Rapoport did not have access to or interest in the meaning of the printed data. In 1977 she wrote, “my work is an aesthetic response triggered by scientific data. The format is computer print-out, a ritualistic symbol of our technological society.”

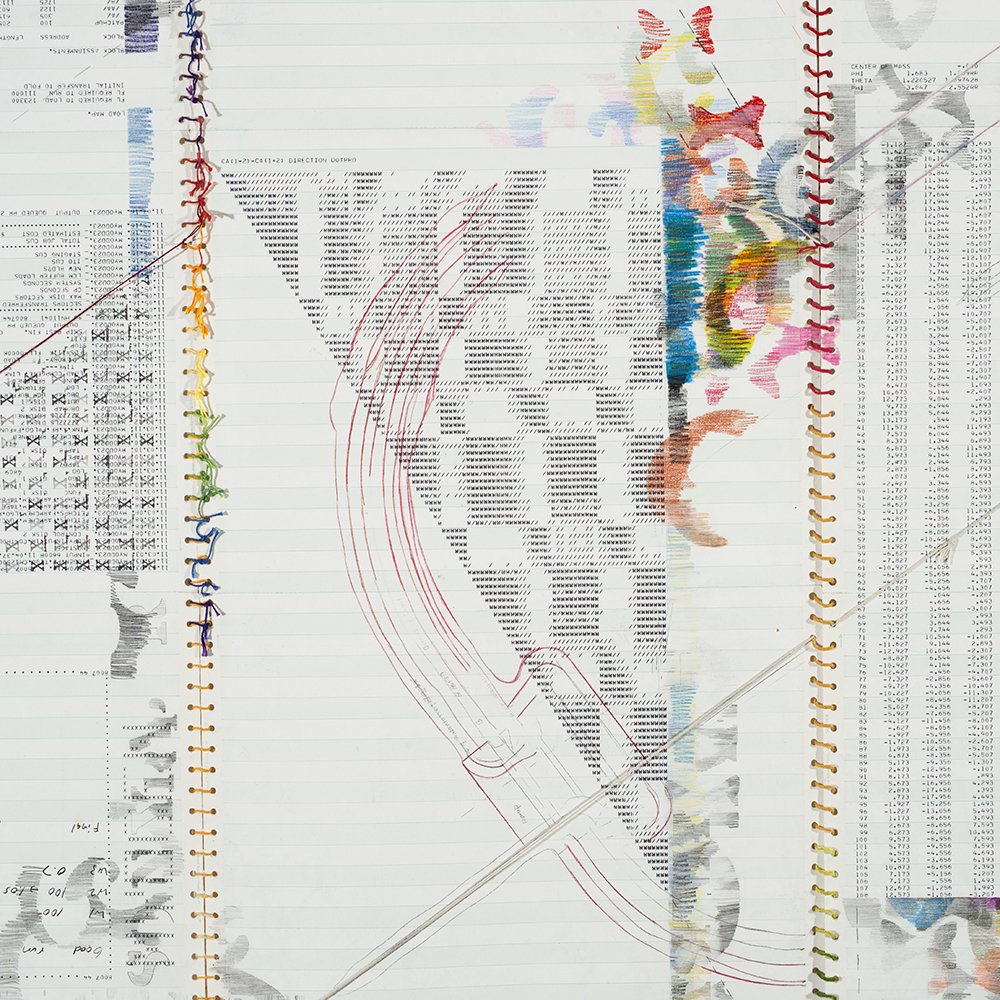

The Yarn Drawings (1976), the earliest of these works, are large scale compositions constructed by stitching together rows of found printout paper with colorful yarn. Rapoport drew into the printed data with graphite, colored pencils, and ink stamps, making use of the Nu-Shu stencils from her earlier work.

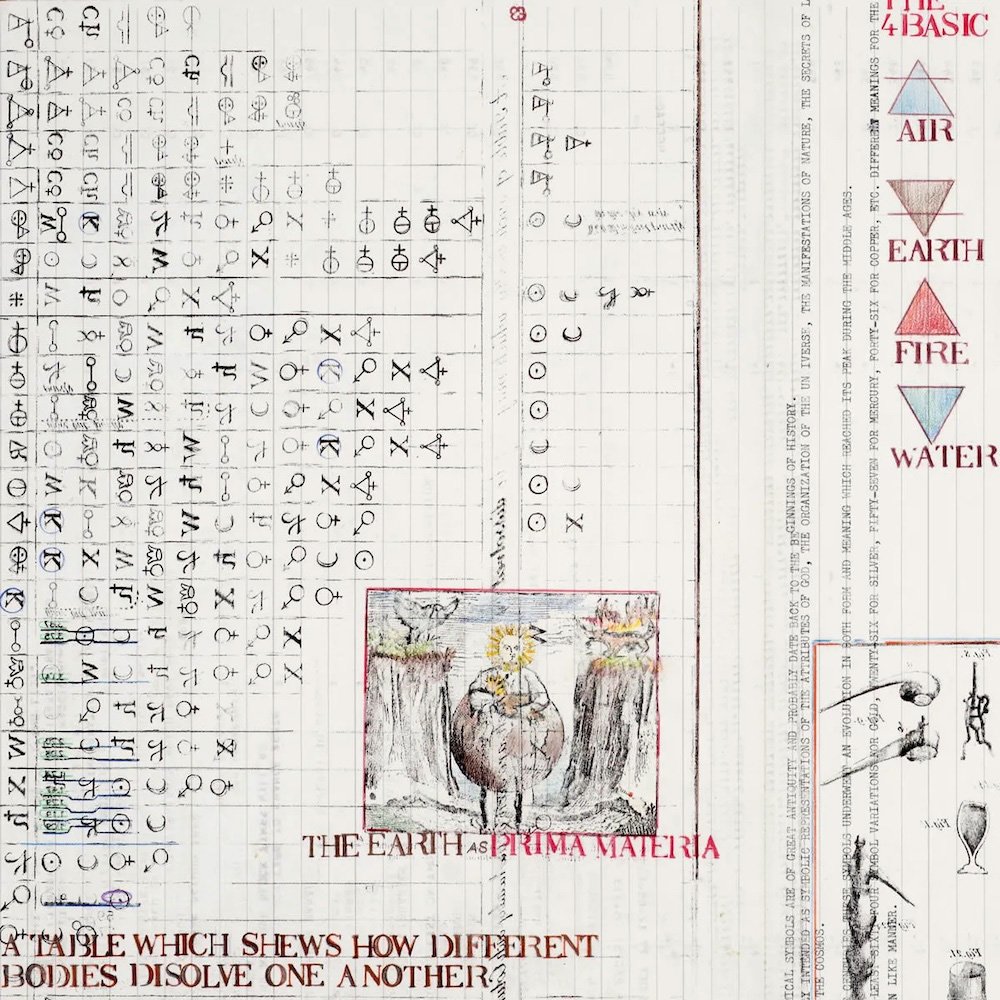

As the series progressed, she became more interested in the computer and the content printed on the papers. In 1977 she began collaborating with anthropologist Dorothy K. Washburn, who shared printed data related to her studies of the ancient Pueblo people of the American Southwest. This led to a series of densely-worked, coded Prismacolor drawings on long scrolls of computer printout paper, including the Anasazi Series (1977).

Meanwhile Rapoport was taking a computer programming course, deepening her knowledge of what would become a critical tool. She began to gather data about her life, especially domestic and traditionally “feminine” concerns, including the rooms of her house, her chinaware, and her shoe collection - what she would later call “soft material.” She then used the computer to analyze this information, printed simple data visualizations using dot-matrix and plotter printers, and then drew into the printouts with colored pencil, typewriter, and solvent transfer techniques.

Energized by this new creative methodology, Rapoport plunged into one of the most prolific periods of her career. She collaborated with a wide variety of scientists, expanded her use of computers, and demonstrated an insatiable desire to synthesize knowledge from wildly disparate fields.

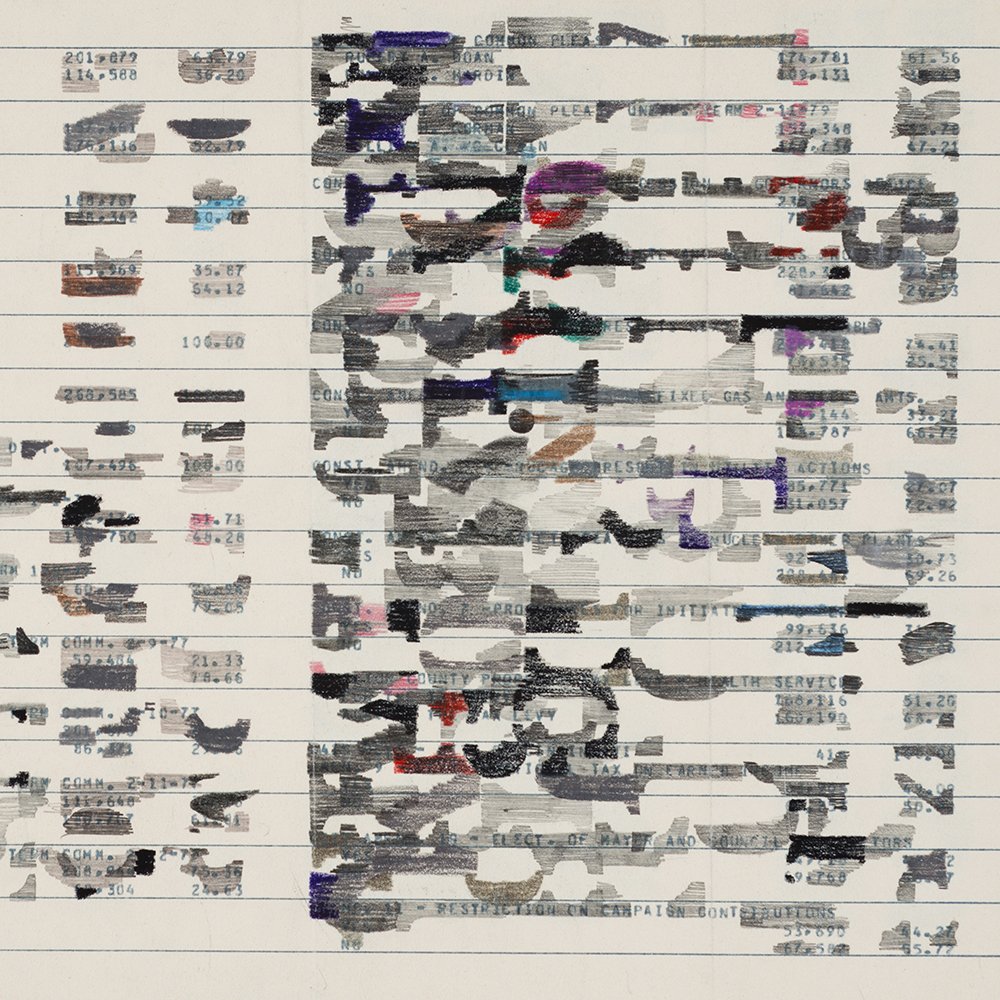

An image of Rapoport from the autobiographical computer printout paper drawing Kiva Studio (1978).