In 1978, building on her Anasazi Series of computer printout drawings, Rapoport began work that left abstraction behind. These drawings made use of copious text and imagery, using the solvent-transfer technique of printing images from photocopies. Incorporating research into anthropology, physics, chemistry, art history, Jungian psychoanalysis and other subjects into her drawings, Rapoport pursued what we might today call a “research based practice.”

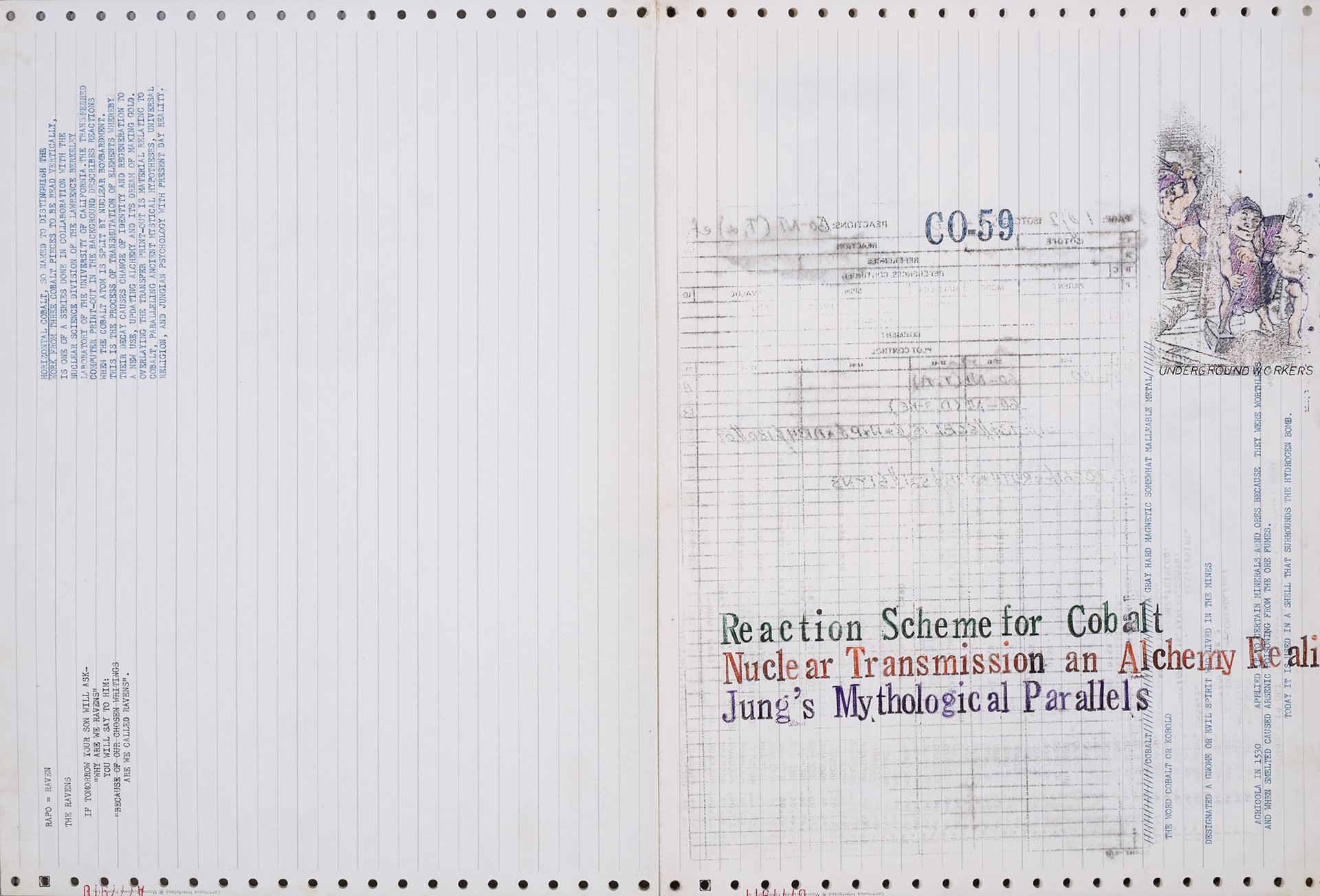

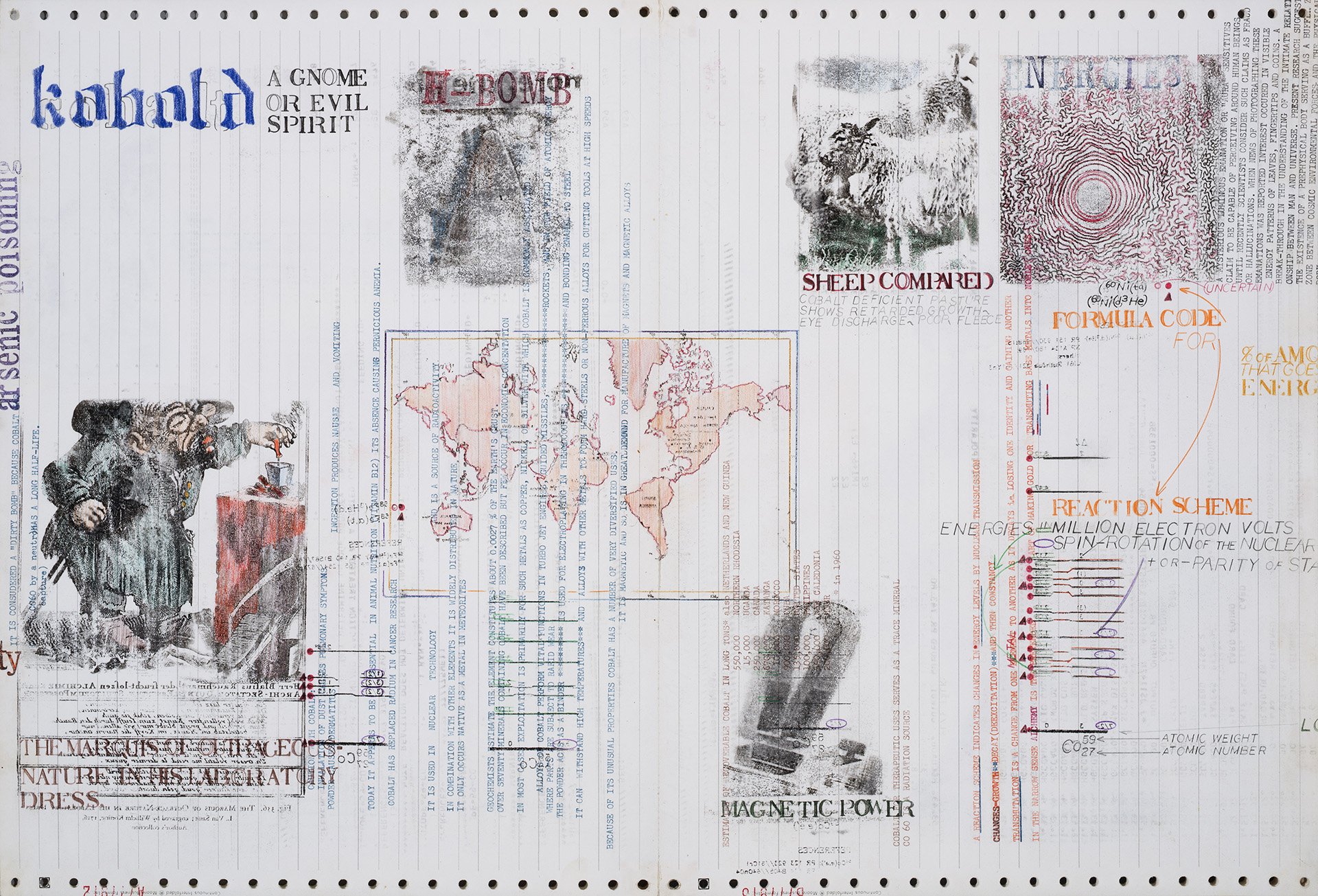

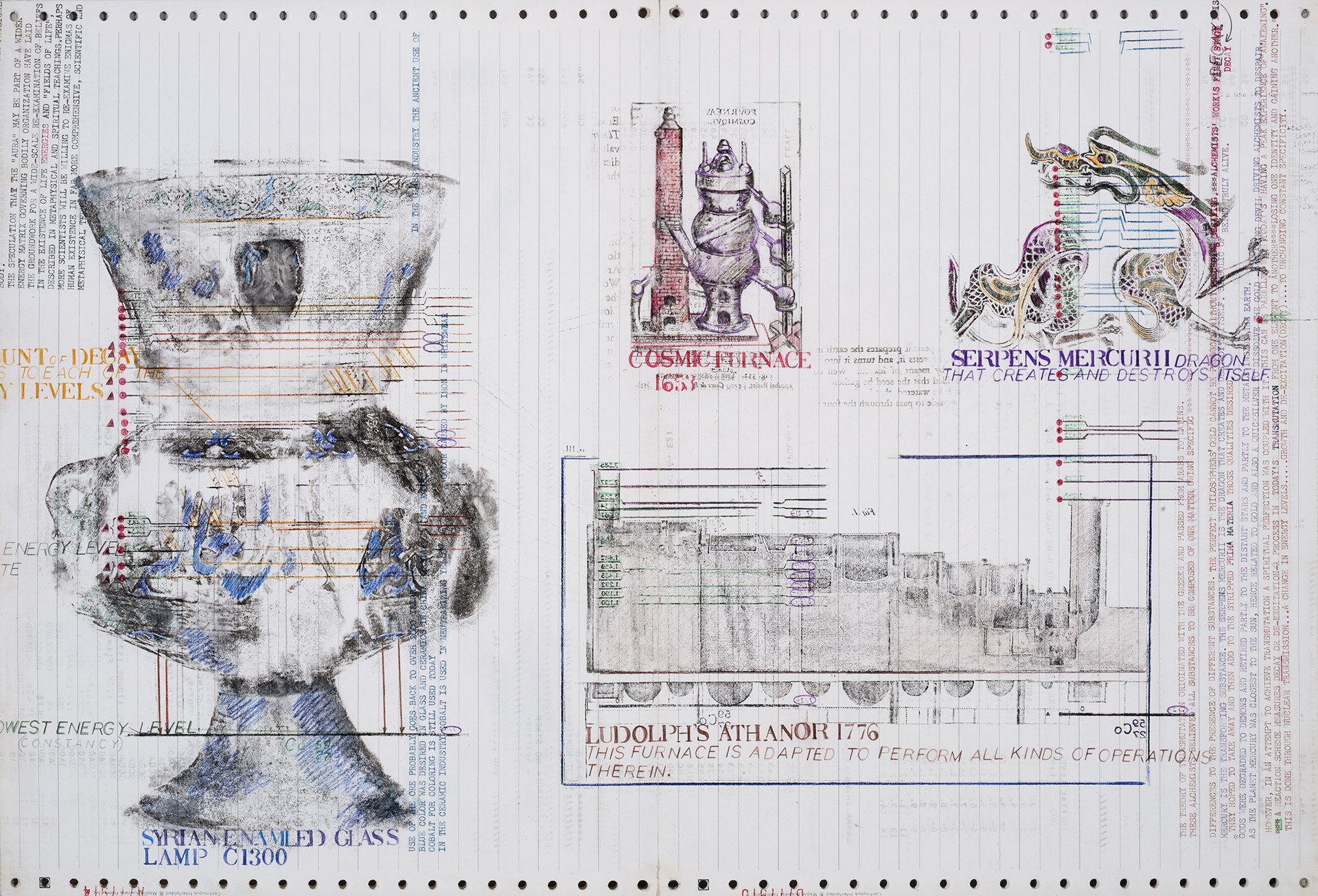

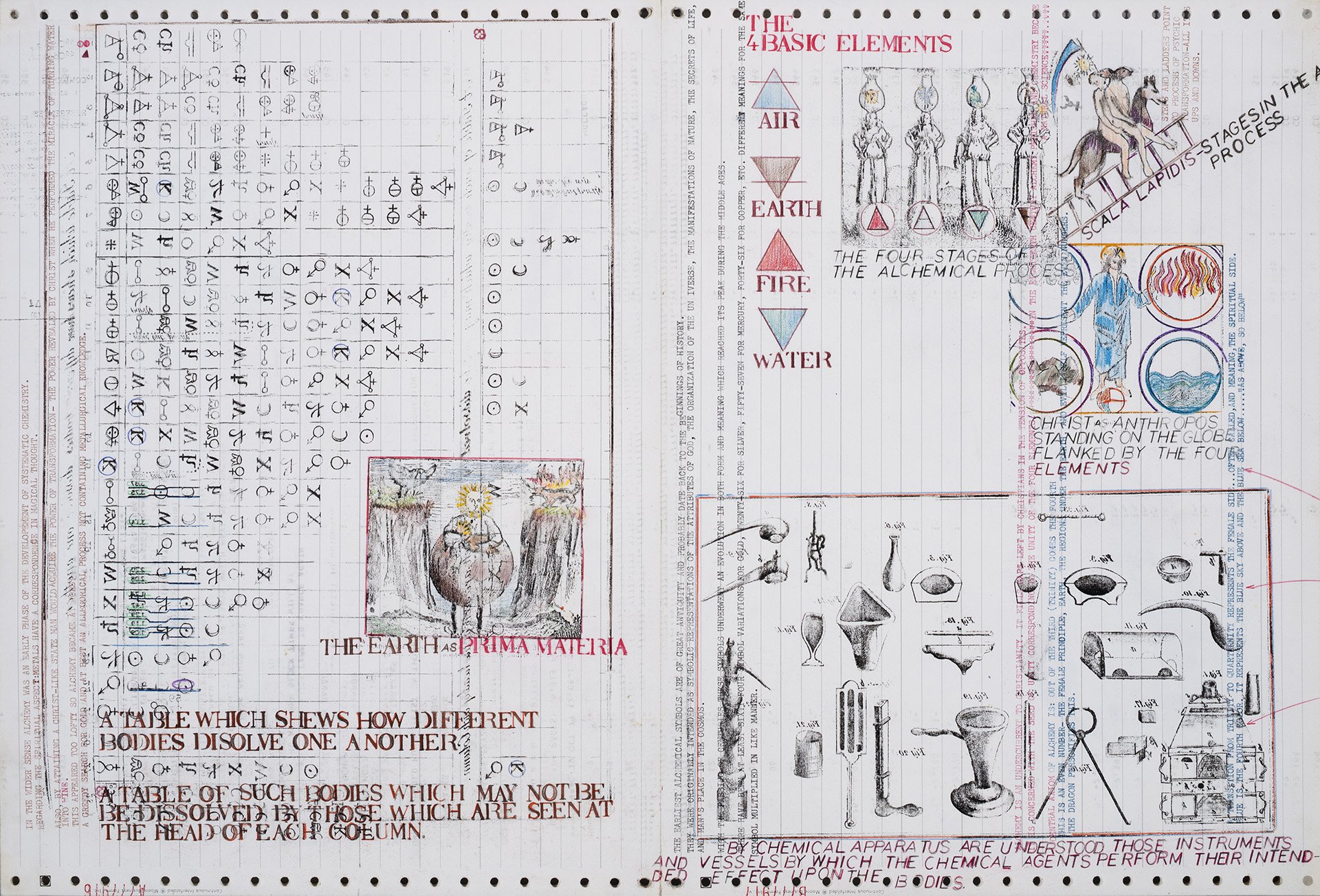

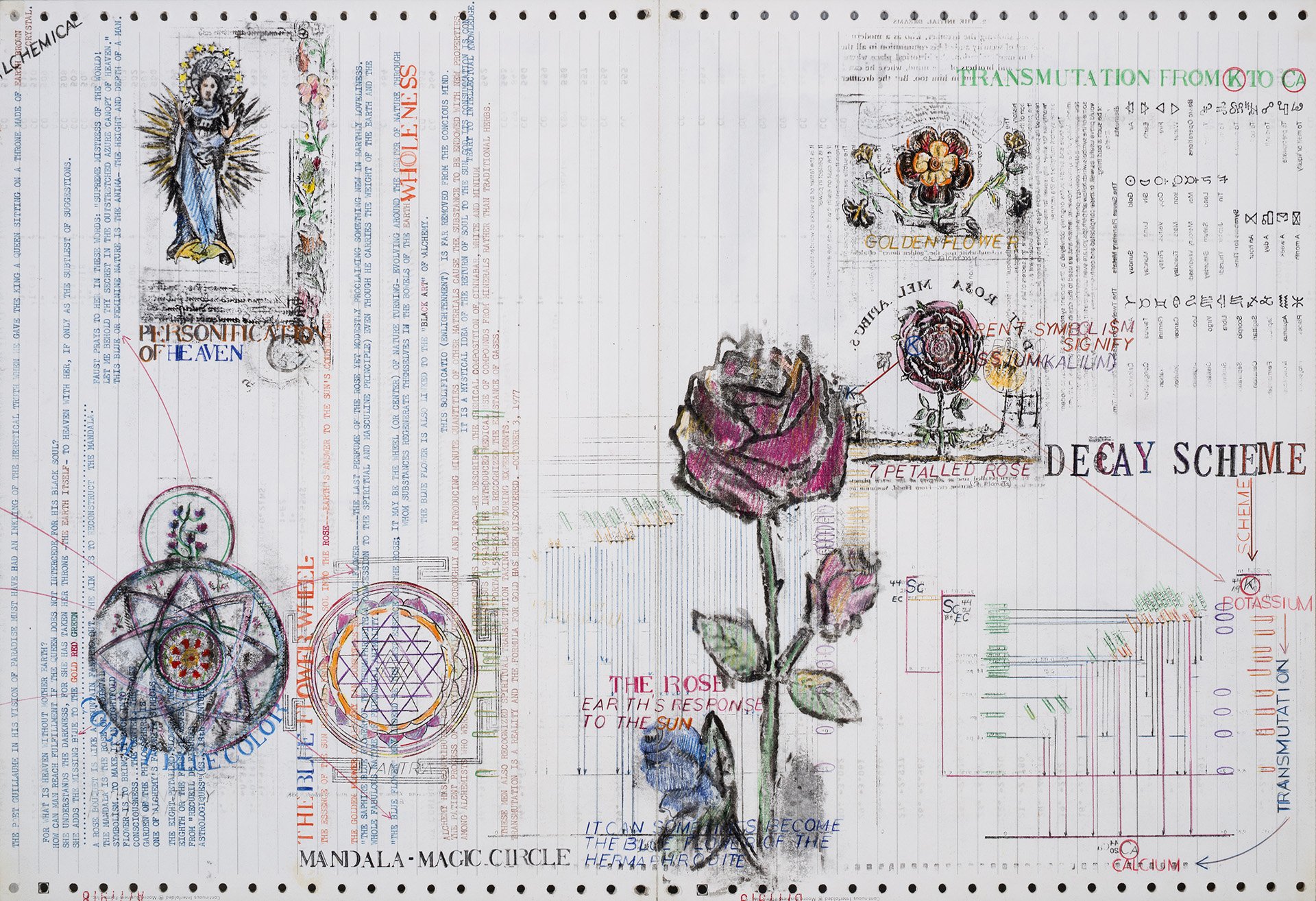

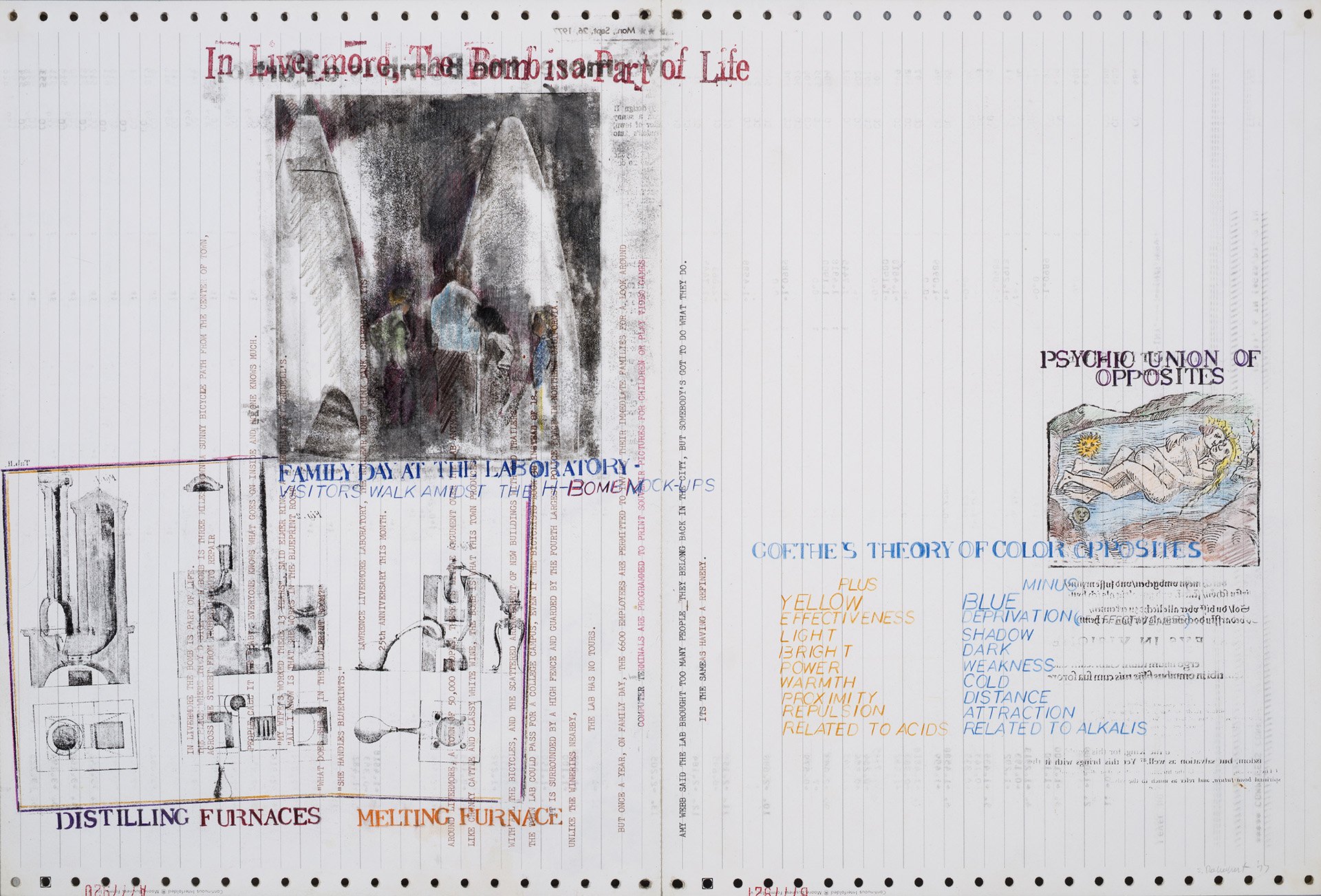

Drawings such as Mercury (1977), and Horizontal Cobalt (1977) exemplify this approach. The latter made use of nuclear science data printed by the Nuclear Science Division of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory that described how they transmuted the element cobalt into gold by bombarding nuclei with neutrons. Rapoport overlaid printouts of their research with hand-colored solvent transfer images that described the history of alchemical transmutation, pagan cosmologies, Kabbalistic mysticism, Carl Jung’s psychological metaphysics, and the history of American nuclear research. The result is a profoundly rich document, overwhelmingly information dense, bursting with arcane imagery, buzzing with interconnections between disparate schools of thought, and alive with humor and wit.

Sonya Rapoport with the work Kiva Studio (1978).

Horizontal Cobalt, 1977. Pencil, Prismacolor, colored typewriter ink, and solvent transfer on continuous-feed computer paper. One folio, 16 pages 11W x 14.875H inches each.

In 1978, Rapoport enrolled in a course at UC Berkeley to learn the programming language Pascal. This prompted the next radical change to her artistic methodology - making use of the computer to gather, analyze, and print her own data.

She began to gather information about her life, especially domestic and traditionally “feminine” concerns, such as the rooms of her house, her chinaware, and her shoe collection - what she would later call “soft material.” She then used the computer to analyze this information, printed simple data visualizations using dot-matrix and plotter printers, and then drew into the printouts with colored pencil, typewriter, and solvent transfer techniques.

Bonito-Rapoport Shoes (1978) exemplifies this approach. It began when Rapoport, researching Dorothy Washburn’s symmetry analysis of Pueblo pottery, encountered an ancient Anasazi sandal. She began gathering quantifiable data about her shoe collection: their shape, style, color, and material, as well as when, where, and why she purchased them. She then entered this data into the computer, and printed graphs that plotted these values with dot-matrix printed ASCII graphs. Working on her custom printouts, she labeled and color-coded the graphs, drew colored pencil drawings of her shoes, each with an index number, and used colored typewriter and solvent-transfer photocopied images to relate a feminist perspective on the history of women’s footwear.

The result is a complex, multilayered drawing where coded data and recognizable images work together to present the results of Rapoport’s visual research in a way that is both highly subjective and quantitatively verifiable.

Bonito Rapoport Shoes, Folio III, 1978. Pencil, Prismacolor, colored typewriter, and solvent transfer on pre-printed continuous-feed computer print, 4 folios, each page 14.875W x 11H inches.

Other works that make use of this approach include Kiva Studio (1978), an extensive autobiographical piece that presents the history of Rapoport’s art practice, and Doors of My House (1978), in which she began using vellum scrolls with plotter-printed data.

These led directly to Rapoport’s most ambitious and extensive work, Objects on My Dresser (1979-83 & 2015), in which Rapoport made use of this approach during the period where she was mourning the death of her mother.